Table of Contents

Welcome to the bustling center of gastric activity—the stomach. Nestled beneath the ribcage, this muscular organ serves as the primary site for the initial stages of food digestion. From its acid-laden depths to the rhythmic dance of peristalsis, the stomach plays a pivotal role in breaking down ingested food into a semi-liquid mixture known as chyme. Join us on a journey into the intricacies of the organ, where digestive alchemy transforms meals into the raw materials essential for the body’s energy and growth.

ANATOMY

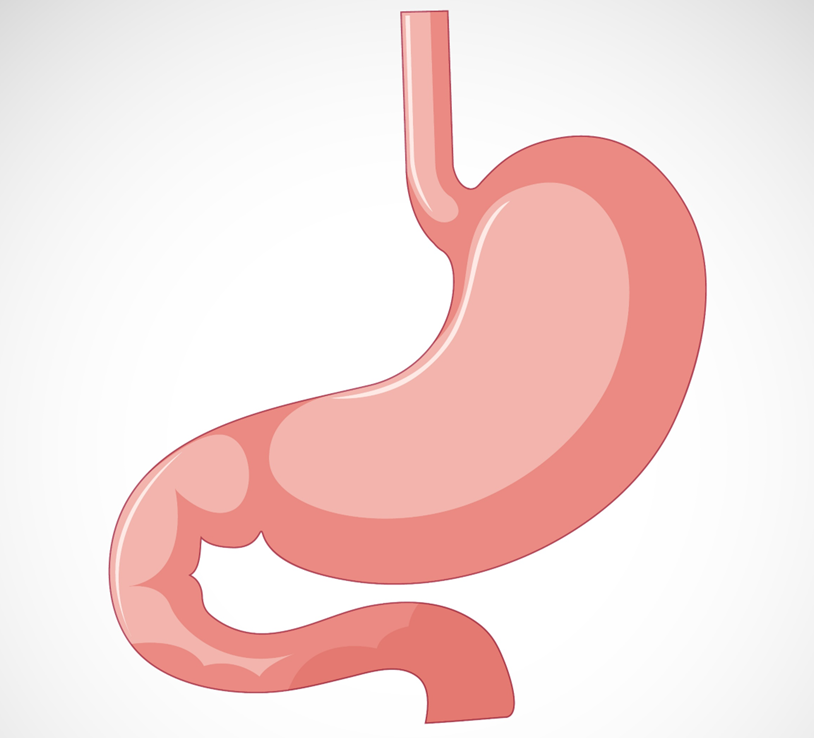

The stomach is a vital organ in the digestive system, playing a central role in breaking down food and facilitating nutrient absorption. Positioned in the upper abdomen, just beneath the diaphragm, the stomach is a muscular, J-shaped organ that connects the esophagus to the small intestine. Its anatomy is characterized by various layers and regions that contribute to its functions.

The stomach has four main regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The cardia is the uppermost part near the esophagus, while the fundus is the rounded portion above the body. The body is the largest region, serving as the main storage area for ingested food. The pylorus is the lower part connected to the small intestine and includes the pyloric sphincter, a muscular valve that regulates the release of partially digested food into the duodenum.

Structurally, the stomach has several layers of tissue. The outermost layer is the serosa, a smooth and slippery membrane that facilitates movement within the abdominal cavity. Beneath the serosa is the muscular layer, consisting of three muscle layers: the longitudinal, circular, and oblique muscles. These muscles work together to churn and mix the food, aiding in mechanical digestion. The submucosa lies beneath the muscular layer and contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves that support the function of the organ.

The innermost layer is the mucosa, a highly folded lining that is essential for the secretion of gastric juices and enzymes. The mucosa contains gastric pits, which lead to gastric glands that produce gastric juice. Gastric juice consists of hydrochloric acid, pepsinogen, and mucus. Hydrochloric acid creates an acidic environment, activating pepsinogen to pepsin, which breaks down proteins. The mucus protects the organ lining from the corrosive effects of gastric acid.

The stomach’s functions include the storage of ingested food, the mechanical breakdown of food particles through muscular contractions, and the initiation of protein digestion through the action of gastric juice. The partially digested food, now called chyme, is gradually released through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine for further digestion and absorption of nutrients.

Blood supply to the organ is provided by branches of the celiac artery, and venous drainage occurs through the portal vein, connecting to the liver. Innervation of the organ involves both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, which regulate various digestive processes.

FUNCTION

The stomach is a vital organ in the digestive system, performing several key functions that contribute to the breakdown of ingested food. Here are the primary functions of the organ:

- Storage: The stomach acts as a temporary storage reservoir for food after it is swallowed. This allows for the controlled release of partially digested food into the small intestine.

- Mechanical Digestion: The organ’s muscular walls contract in a coordinated manner, initiating mechanical digestion. This churning action helps break down large food particles into smaller fragments.

- Chemical Digestion: Gastric glands within the stomach lining secrete gastric juices containing hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes, including pepsin. These substances contribute to the chemical breakdown of proteins into smaller peptides.

- Acid Secretion: Hydrochloric acid (HCl) is produced by the stomach lining to create an acidic environment. This acid not only aids in the digestion of proteins but also helps kill potential pathogens in ingested food.

- Activation of Pepsinogen: Pepsinogen, an inactive precursor, is released by gastric chief cells. In the acidic environment of the organ, pepsinogen is converted into its active form, pepsin. Pepsin plays a crucial role in protein digestion.

- Intrinsic Factor Secretion: Intrinsic factor, produced by gastric parietal cells, is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

- Limited Absorption: While the stomach is not the primary site of nutrient absorption, it can absorb certain substances, such as alcohol and some medications.

- Initiation of Carbohydrate Digestion: Salivary amylase, which begins the digestion of carbohydrates, continues to work in the stomach until it is inactivated by the acidic environment.

- Regulation of Gastric Emptying: The organ regulates the release of chyme into the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter. This helps ensure that the small intestine receives a manageable amount of partially digested food for further processing.

- Secretion of Mucus: Mucus-producing cells in the stomach lining secrete a protective layer of mucus, preventing the organ from digesting itself and providing a barrier against the corrosive effects of stomach acid.

DISEASES

The stomach can be affected by various diseases and conditions that may impact its structure and function. Here are some common diseases and disorders associated with the organ:

- Gastritis: Inflammation of the organ’s lining, which can be acute or chronic. It may be caused by infection, certain medications, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disorders.

- Peptic Ulcers: Open sores that develop on the inner lining of the stomach, the upper part of the small intestine, or the esophagus. Most peptic ulcers are caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria.

- Gastroenteritis: Inflammation of the stomach and intestines, often due to viral or bacterial infections. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): A chronic condition where stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, leading to symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain.

- Gastric Cancer: Cancer that originates in the lining of the organ. It is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, and risk factors include Helicobacter pylori infection, smoking, and certain dietary factors.

- Stomach Polyps: Abnormal growths on the inner lining of the stomach. While most stomach polyps are benign, some may develop into cancer over time.

- Gastroparesis: A condition where the organ takes longer than normal to empty its contents into the small intestine. It can result in symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

- Erosive Esophagitis: Inflammation and damage to the esophagus caused by stomach acid flowing back into the esophagus. It is often associated with GERD.

- Stomach Stricture: Narrowing of the stomach opening or the pyloric sphincter, which can lead to difficulty in food passage from the stomach to the small intestine.

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: A rare condition where tumours in the pancreas or duodenum cause excessive production of gastrin, leading to increased stomach acid production and peptic ulcers.

- Stomach Perforation: A serious condition where there is a hole or tear in the organ’s wall, allowing the contents of the organ to leak into the abdominal cavity. It requires immediate medical attention.

- Functional Dyspepsia: Chronic indigestion or discomfort in the upper abdomen without an apparent cause. It can include symptoms such as bloating, fullness, and early satiety.

If you experience persistent symptoms such as abdominal pain, indigestion, or changes in bowel habits, it’s important to seek medical attention for a proper diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

HEALTHY STOMACH

Maintaining a healthy stomach involves adopting lifestyle habits that support digestive well-being. Here are some tips to help keep your stomach healthy:

- Eat a Balanced Diet: Include a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats in your diet. A balanced diet provides essential nutrients and supports overall digestive health.

- Hydrate Adequately: Drink sufficient water throughout the day to support digestion and prevent dehydration. Limit excessive consumption of caffeinated and sugary beverages.

- Practice Portion Control: Avoid overeating and practice portion control. Eating smaller, more frequent meals can help prevent excessive strain on the stomach.

- Chew Food Thoroughly: Chew your food thoroughly to aid in the digestive process. This helps break down food into smaller particles, making it easier for the stomach to process.

- Limit Highly Processed Foods: Reduce the intake of highly processed and sugary foods, as they may contribute to inflammation and disrupt the balance of gut bacteria.

- Moderate Alcohol Consumption: Limit alcohol intake, as excessive alcohol can irritate the organ’s lining and contribute to conditions like gastritis and ulcers.

- Quit Smoking: If you smoke, consider quitting. Smoking can increase the risk of developing stomach ulcers and other digestive issues.

- Manage Stress: Practice stress-reducing techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, or yoga. Chronic stress can contribute to digestive problems.

- Stay Active: Engage in regular physical activity to promote overall health, including digestive health. Exercise helps maintain a healthy weight and supports digestive function.

- Avoid Late-Night Eating: Allow a few hours between your last meal and bedtime to give your stomach time to digest food. Late-night eating can contribute to acid reflux and indigestion.

- Hygienic Food Handling: Practice proper food hygiene to reduce the risk of foodborne illnesses, which can affect the stomach and digestive system.

- Limit NSAID Use: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can irritate the organ’s lining. If needed, use them under the guidance of a healthcare professional and avoid excessive or long-term use.

- Stay Hygienic: Wash your hands thoroughly before eating or handling food to prevent the spread of bacteria that can cause stomach infections.

In conclusion, the stomach stands as a dynamic hub in our digestive symphony, orchestrating the initial acts of food breakdown with precision and prowess. By embracing mindful eating habits, staying hydrated, and cultivating a lifestyle that supports digestive harmony, we empower this resilient organ to function optimally. May your journey through the exploration of stomach health be one of balance, nourishment, and sustained well-being.